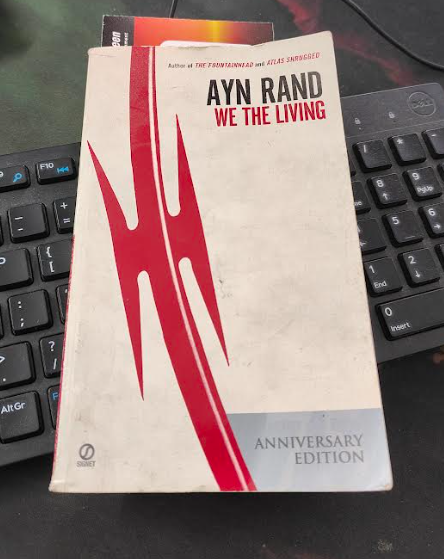

I have this inherent pull towards classic literature that I try to read at least one classic every three months, else, something is missing in life. There’s something about them that I still can’t explain, the time-worn pages, the echo of old thoughts, the slow paced plotlines, and at times, the characters are also slow in terms of how they operate in their respective worlds. Every revisit feels like a reunion with long-lost companions. I find myself re-acquainted with characters with a feeling that we might have when we meet our friends with whom we shared camaraderie at junior school. This time, I returned to We the Living – Ayn Rand’s first and, in many ways, most emotionally resonant novel.

Published in 1936, We the Living is often overshadowed by Ayn Rand’s more famous works like Atlas Shrugged and The Fountainhead. However, reading it twice reveals that it has something they lack: a raw and powerful emotion, like an unpolished diamond still covered in dirt from the mine. It’s a story influenced by Rand’s own life, not just ideas or theories. She herself described it as the most personal reflection of her thoughts and feelings, not about specific events, but about her inner spirit.

The Individual vs. the State

The story takes place in Soviet Russia after a revolution. The setting includes scenes like long lines for bread, changed propaganda films, and apartment buildings where many families are sharing the same apartment but residing in different rooms, which means privacy no longer exists. These details are real, and they serve as the background. The main focus, however, is the ongoing struggle between a person’s individual identity and the powerful, controlling government.

This very struggle finds a darkly satirical parallel in Kurt Vonnegut’s Harrison Bergeron, where the state enforces equality through crude handicaps, punishing intelligence, beauty, and strength to maintain ideological balance. Just as Rand’s characters are slowly suffocated by the collectivist machinery of the Soviet system, Vonnegut’s vision imagines a world where the erasure of the self is achieved not through fear alone, but through absurdity. In both cases, the individual becomes a threat, and ultimately a sacrifice, to the illusion of societal harmony.

The Characters

The protagonist, Kira Argounova is a young woman who simply wants to become an engineer, to create, to live her life, and to love, on her own terms. But in a society that views individuals as replaceable and the state as all-powerful, her dreams are seen as rebellious. Her loves, first for Leo, and later her complicated relationship with Andrei, are not just part of the story but also express her inner struggles. She is like a fortress that the powerful system cannot break down, though her body might be hurt, her spirit never gives up.

Leo Kovalensky, her boyfriend, is one of the most tragic characters in all of Rand’s books. At first, he is full of energy, confidence, and a desire to stand out as an individual. But over time, he slowly fades away. The gradual hardships of life burn him down in slow erosion. His descent echoed that of Josef K. in The Trial, not brought down by a single act, but buried under the quiet absurdity and invisible violence of a system that thrives on unreason. Leo depends on Kira’s support to keep going, and when he loses it, he loses himself.

Andrei Taganov, a high-ranking Party official who falls in love with Kira, is a very interesting and complex character. He is a revolutionary who believes in working for the common good and placing others before himself. However, his love for a woman makes him see that the idea of putting everyone together to help each other may not be as perfect as he thought. When he realizes that trying to make everyone equal can actually destroy people instead of helping them, his decision to take his own life becomes a way of showing his true beliefs, which is, being completely honest with himself. His journey reminds me of Raskolnikov in Crime and Punishment by Dostoevsky. Both (Andrei and Raskolnikov) are driven by ideology, they live not merely as individuals but as representatives or adherents of larger philosophical systems. Yet, both eventually face disillusionment with those beliefs.

The Second Reading Hurts More

What makes We the Living even more meaningful when you read it again isn’t just understanding the story better, but noticing its deeper themes. The first time I read it, I saw the sadness and tragedy. The second time, I saw a warning about what can go wrong. The novel is saying that even the most honest and noble ideas, when turned into institutions and power, can end up destroying everything. Rand makes this idea very personal, it’s about your family, your dreams, your body, and your very life.

There are heart wrenching moments, which made me pause and reflect. In fact, I found myself empathizing with the victims here, like a young girl watching her father fall from grace, a desperate plea in a hospital hallway, a funeral where the state praises a man it destroyed. These are knife-thin slices of pain, clean and efficient.

Not Just Oppression, But Erosion

Thematically, the book shares DNA with a host of other anti-totalitarian works, some of those are, Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, here focus is on soft totalitarianism, control through pleasure, conditioning, and the suppression of individuality via comfort and conformity, rather than fear, which is the case with We The Living. And Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451. This book is about censorship, intellectual repression, and the erasure of individual thought. Like We the Living, it mourns the loss of personal identity and intellectual freedom under conformity.

However, Rand’s characters resist not through rebellion or escape, but through love and purpose. Kira’s engineering ambitions aren’t just career goals, they’re her defiance, her declaration that the mind, not the collective, is sacred.

What makes We the Living stand out is how it connects with our feelings. If Atlas Shrugged is a celebration of logic and reason, then We the Living is like a heartfelt farewell to the human spirit. Its sadness feels real and piercing, even the supporting characters like Irina, who has accepted her bleak future, or Victor Dunaev, a clever Soviet thinker who just repeats empty slogans, help show a society struggling with moral confusion.

This book is not about criticizing the Soviet system, rather it shows what it does to people, the ones we might have cared about or even been.

The Novel That Fought to Be Published

The thematic resonance is further amplified by the novel’s publication history. The book was initially rejected by multiple publishers, which shows that the story of We the Living is not just within its pages, but in the fact that it exists at all.

One particularly striking scene, and one I didn’t remember until I read it again, involves a foreign movie that was secretly brought into the country. The Soviet censors changed the subtitles to turn its message upside down. The audience, who were smart and experienced, watched the movie and paid attention to the story rather than the words. They even laughed at the wrong parts, which suggests that even under an oppressive regime, the human mind still searches for truth, and individual judgment cannot be fully extinguished.

It’s a simple but powerful scene that shows how strict governments can’t completely crush people’s ability to think for themselves, at least not completely.

The Enduring Power of We The Living

Ultimately, We the Living is more than just a story about politics. It’s also a love story. At its core, it’s a heartfelt plea for respecting and valuing each person’s individuality. It’s a book about the simple act of breathing, set in a world where that freedom has been taken away. The book is a powerful epitome of how ideology, when not tempered by empathy and individuality, becomes a machine that grinds down the human soul.

It’s not an easy or comfortable read. But I think it’s an important one, especially for those of us who believe that stories should do more than just entertain. They should teach, make us think, stay with us, and sometimes even shake us up. No wonder I chose to read this one again — and I’m sure I will do so again in a few years. Some books don’t just stay with you; they grow with you.